Historically, the most intimidating figure is a woman who knows her worth. The inability to drown her independence, stubbornness, and worst of all: her sexuality, is universally feared. For women, society’s definition of what you can be is limited to how you exist as a sexual being. Expectations to be sexy, but not too sexy; dominant, but not so much that she challenges masculinity; submissive, but not in a way that makes conquest easy. In short, women are expected and trained to conform to male-set guidelines. With deviation emerge accusations that come in multiple flavors, like “slut,” or “prude.”

Although both represent anger fueled by a female’s choice in how she expresses sexuality, being a “slut” is arguably the harsher of the two, considering it implies a woman’s sexual behavior, rather than her lack thereof. To speak bluntly, it is much easier for society to forgive virginity than promiscuity. Of course, the negative stigma (or, for this specific example: slut-shaming) around female sexuality is not limited to sexual intercourse and actual acts of sexual behavior. Slut-shaming is a common occurrence for women, regardless of elements such as marital status, virginity, faithfulness in relationships, and so on. Simply put, for females, this is a generally unavoidable experience.

Perhaps the best to illustrate exactly what that means is the Queen of Pinup herself: Bettie Page. Page was extremely intelligent, hardworking, talented, beautiful, and faithful. On paper, she was everything a woman was expected to be. As a child, she dreamed of becoming an actress, her vivid imagination providing comfort and fun for herself and others as she grew up during the Great Depression. This dream carried on into her adult life, although she gave it up to stay with her husband and become a teacher, hoping to use some of her theatrical talents in such a setting, considering that profession also hinged on her creativity and public speaking abilities. However, Page was harassed by her male students, the argument being that her appearance and hourglass figure were “too distracting.”

Eventually, Page moved to California, where she began to pursue her dreams once again while her husband was deployed overseas. As he returned, the couple divorced. Page acknowledged that she could never be truly happy as nothing more than a housewife, like her husband expected her to be. She would go on to work in New York as a secretary, and eventually found herself modeling. She treated modeling like a business, and actually set the framework for how models are expected to behave today, including the exercise habits, diets, and other self care measures.

Although she faced dozens of hardships, Bettie Page stayed true to her own moral compass, offering up an image of herself as a woman who knew her worth. As her pinup career as a model exploded, she became the subject of significant scandals. Tarnishing her standing as a professional forever was the accusation that she was involved in pornographic films. Of course, the accusations were false, but the damage was done, and her reputation ruined. Bettie Page is the poster child for the destructive effects of slut-shaming on women, its practice indiscriminately devastating the lives of its targets.

Slut-shaming in pop culture, as with the case of Bettie Page, is important to acknowledge and call out. However, it is just as, if not more, important to acknowledge the everyday reality of slut-shaming. It is important to note that although women are the targeted majority of this harmful attention, this kind of shaming is not limited to them (although it is far more acceptable for men to engage in sexual behavior, as long as it is heterosexual. In fact, it is encouraged and expected for straight men to be sexually active). Where for some, slut-shaming just comes with general existence, there is one target that experiences something that can almost be described as institutional slut-shaming: prostitutes (or sex workers).

As stigma is inherent in professions that revolve around sex, I will be specifically discussing the social consequences of prostitution/sex work, focusing on the differences between the United States, where sex work is mostly illegal, and the Netherlands, where sex work has been legalized. Although sex work and prostitution are the same practice, I will be referring to them based on their legal status. For the U.S., it will be prostitution. For the Netherlands, sex work.

The topics of prostitution and sex work are very loaded, because sexuality is a universally feared topic. To limit the scope of this article, I will be focusing on civil rights for prostitutes and sex workers, the causes of criminalization associated with these practices, male prostitution and sex work, the HIV risks, and public opinion and reactions in both countries

Fights for Civil Rights

For the United States, one of the most notable pushes for civil rights regarding prostitution occurred in the 1970’s, with a group that called themselves “COYOTE,” short for “Call Off Your Old Tired Ethics,” leading the charge. In his journal, Prostitute’ Rights In The United States: The Failure of a Movement, Ronald Weitzer outlines the COYOTE’s goals: “(1) public education regarding the costs of existing prostitution controls, (2) decriminalization of all aspects of voluntary adult prostitution, and (3) normalization of the occupation and the individuals involved in prostitution (24).” It is important to acknowledge that the group actually opposed the legalization of prostitution- they favored decriminalization above all else. This step is necessary in achieving the end goal of normalization. By achieving normalization, there is significant stigma removed. In fact, Weitzer makes creates interesting imagery by quoting COYOTE’s director, who says, “Once they don’t go to jail, they can come out of the closet and be normalized (27).” The significance of this quote can be related back to Erving Goffman’s Stigma, specifically to the discussion of passing. The concepts of “the closet” and “passing” are in the collective imagination today being associated with the LGBT+ community. If that is the association we typically have, what significance do these terms have with issues like prostitution?

Before answering that, it is important to understand that there are two kinds of passing that Goffman describes. The first type is a “stigmatizing affliction possessed by an individual…known to no one, including himself,” and the second being stigma that is “nicely invisible and known only to the person who possesses it, who tells no one (73).” Regarding COYOTE’s goals, the normalization of prostitution means that prostitutes are able to pass in everday life. No one else is aware of their stigma, because the formerly stigmatizing practice has been reformed in the eyes of society.

Now, Weitzer gives away the ending of the story before you even have a chance to open the book, acknowledging the failure of the movement. Living in the United States now, we are very aware of the status of prostitution and the stigma that it carries. COYOTE was, unfortunately, unsuccessful, as it did not “alter public opinion, nor won major concessions or lasting acceptance from authorities (Weitzer, 36).”

Where the United States failed, the Netherlands experienced some success. The most important note to make here is that where COYOTE sought the decriminalization of prostitution, the Netherlands opted for legalization in 1999. With legalization, you see the shift from prostitution to sex work, the important element here being the introduction of regulation. Regulation is one of the main reasons why the United States chose to fight for decriminalization instead, as it was believed that the more restrictions introduced would bring more power to pimps and make it even more difficult for the prostitutes themselves.

The Netherlands chose the legalization route as a means to fight trafficking, and make sex work safer. The principal fight was to create a distinction between voluntary sex work and forced prostitution. With this came requirements for sex workers, including the need to “register with the authorities, the age to work in the sex industry is to be raised from 18 to 21 years, and clients will have to check whether the sex worker is registered and not an ‘illegal’ worker (Outshoorn, 233).” These regulations appeared to be fantastic steps towards tackling the issue of sex trafficking, and there were even some benefits that COYOTE never seemed to even consider, which was the acknowledgement of sex work as legitimate business. Local authorities were responsible for the health and safety requirements, and “sex workers became eligible for social rights as well as for paying taxes and social insurance (242).”

Where all of this is wonderful on paper, the truth must be acknowledged. After legalization, the state of sex work in the Netherlands was frightening. Sex trafficking was still a major concern, and abuse was rampant throughout the sex industry. Where the largest difference between the Netherlands and the United States falls into the category of legalization vs. decriminalization, it is unavoidable to discuss that most sex workers in the Netherlands prefer to remain anonymous, considering the incredible stigma they face, although their line of business is no longer viewed to be illegal.

Regarding civil rights, the United States’ attempt was a failure, although COYOTE paved the way for reform, being noted for improving the situation of American prostitutes. For the Netherlands, attempts were technically successful with the legalization of sex work, but as of the early 2000s, there was still a long way to go before sex workers could expect genuine improvement regarding their social standings.

Causes of Criminalization

As previously mentioned, the United States chose to look at the rights of prostitutes through the lens of decriminalization. COYOTE’s time was in the 1970s and 80s, but new waves of calls for the decriminalization of prostitution pop up occassionally in everyday American life. Why is that?

According to Ronald Weitzer, there is a positive correlation with the use of the Internet and the “mainstreaming” of the sex industry, especially regarding the availability of things like pornography. In his article, The Movement to Criminalize Sex Work in the United States, he illustrates that in November 2008, there was a ballot measure that would have been able to decriminalize prostitution in the city of San Francisco, California. Although the measure failed, it was supported by a “sizeable minority of voters- 42 percent (61).” With this information, it would appear that although we are not there yet, the tide is turning in favor of prostitutes. However, as something as controversial as sex work and prostitution come up to the general public, those opposed dig their heels in the ground and stand stronger than before against the perceieved threat. Here enter the moral crusaders.

Weitzer himself discusses them, but I’m going to be focusing on how Howard S. Becker tackles this group. For Becker, moral crusaders operate with an “absolute ethic; what he sees is truly and totally evil with no qualification. Any means is justified to do away with it (148).” Generally, the moral crusaders for matters regarding sex are religious influences, and this is true for the fight to decriminalize prostitution. However, the key point to take away from these crusaders in this context is the scapegoat- the golden goose that cannot be fought against and is viewed as an automatic win. As will come up in any conversation across borders regarding prostitution, the biggest reason to fight against sex work is the fear of sex trafficking.

Surprisingly, the Netherlands does not share the same kinds of fears as the United States, although as previously mentioned, sex trafficking was a major influence in the legalization of sex work. The term “criminalization” is not fair to the Netherlands, because it was not really criminalized. That is not to say, however, that there has always been widespread support for sex work. One of the largest defenses against it was less focused on fear and potential dangers, but on the disruptions to family life. Inititally, “Men were thought to need opportunities to have sex outside marriage: a biological sex urge that should not be suppressed (Boutellier, 202).” As time went on, this kind of behavior was considered less acceptable, becoming considered a “perversion.”

Interestingly enough, it was medical professionals that were among some of the lead players in acquiring more restrictions to sex work- they were the ones that introduced the word “perversion” to the public imagination. A theoretical approach Howard S. Becker discusses as a source of deviance is pathology. It was argued that the source of deviancy came from inside the individual, and that things like mental illness could explain abnormal behavior. However, sex work was not viewed as the result of a pathological defect. In fact, it is significant that sex work in the Netherlands was not based around the sex workers themselves at all. There was much more of a focus on accountability for those who ran the brothels and those who purchased the service in the first place. The reason for medical intervention in this topic was the call for healthy sex workers.

Unfortunately, “healthy” was synonymous with abstinence. Although this is technically true, as we know today, abstinence based models of sex education do…nothing. The anti-prostitution movement held this, among other beliefs, at the front in an attempt to legitimize their cause.

“Criminalization” isn’t really a fair word to compare these two countries and their approaches in the anti-prostitution movements. However, it is important to note that sex work and prostitution have been publicly and legally challenged through interested groups speaking out and advocating, the basis behind each fight being fear of sex trafficking for the United States, and fear of disrupting the expected family life.

Male Prostitution

Sex work and prostitution are heavily associated with females. The images of a girl on a street corner or a dominatrix are fairly universally understood. However, it is irresponsible to ignore the fact that there is a male presence in these ways of life.

Now, the most important thing to notice about this topic is the severe lack of research on male prostitution. Generally, a search on the subject will turn up with dozens of articles about men who buy sex, but very few on those who sell it. This in itself is a danger because it creates a similar kind of environment that is around male domestic abuse victims. The mindset of, “That doesn’t happen to men” is a really toxic and dangerous one. Yes, this is a mainly female issue, but that by no means limits the pool of people involved in it. That being said, it is important to know the different names for these services. For males, the term “escort,” as opposed to “prostitute” or “sex worker” provides many more results and insight.

For the United States, studies have been done that have revealed the main market for male escorts/prostitutes is other men. Generally, gay and bisexual men make up a majority of this population. Regarding the difference between escorts and prostitutes, escorts are able to be more selective with their clientele, and are seen as a much more legitimate business. In his article, Sexual Compulsivity Among Gay/Bisexual Male Escorts Who Advertise on the Internet, Jeffery T. Parsons states, “Escorts now have web sites, which include photos and descriptions of their services, and potential clients are able to e-mail these escorts or find them in popular Internet chat rooms (102).”

Thanks to the internet, the ability to choose, filter, and advertise for clients creates a level of safety and security unavailable to prostitutes and traditional sex work. With the legitimacy of the escort business, what would previously be considered prostitution is now recognized sex work.

Although sex work is legal in the Netherlands, the escort agencies still do well. As in the United States, these also have high numbers of male workers. However, legalization brings an interesting point of view to this topic, because there are multiple kinds of legitimate businesses in this field. How do escort agencies stick out? Simply put, there appears to be a positive correlation between the convenience of the internet and escort services. A.L. Daalder basically summarizes the relationship between clients and escorts by saying, “Typical for an escort agency is its mediating role between the customer and the prostitute. Contact is usually established via the internet, social media or by telephone (17).” Similar to the United States, the male escorts in the Netherlands also tend to be gay men.

During the 2000s, escort agencies increased while the vast majority of all other kinds of sex work have decreased. Below is an infographic to support that claim.

Both the United States and the Netherlands have begun to embrace this new line of sex work possible only through utilization of the internet.

HIV Risks

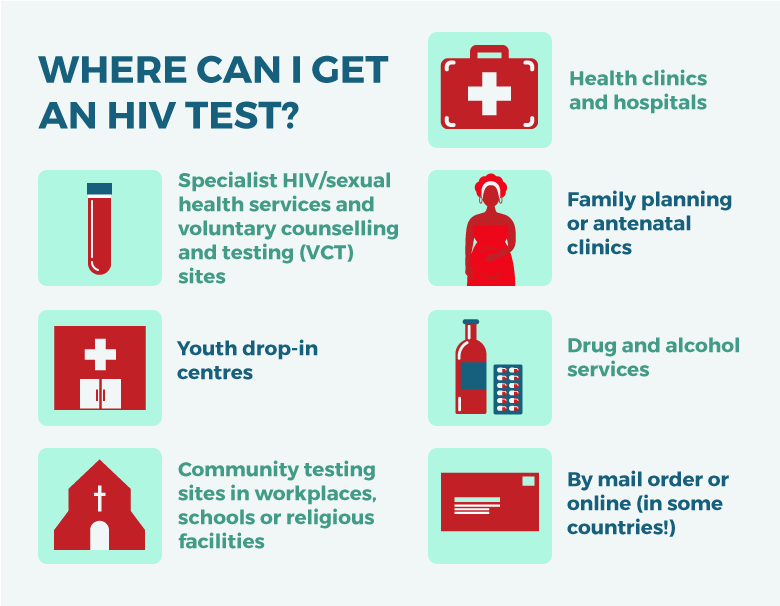

Venereal diseases are a huge risk for any sexually active individual. However, when your profession is sex, staying healthy and being aware of your status with the different kinds of potential infections and diseases should be at the forefront of a prostitute and pimp’s mind. Not only is this important for the worker themselves, but it’s also a necessary measure to protect clients. I am going to focus mainly on HIV for the purposes of this article, specifically discussing how aware prostitutes and sex workers are of their status.

There is a crippling stigma around HIV, especially in the United States, based on our history with the AIDS crisis. Not only is it infamous for being essentially a death sentence in the 1980s, but there is also a strong association to the LGBT+ community and all the stigma and discrimination that group experiences. HIV/AIDS relates strongly to the concept of passing in this context. A positive diagnosis was a way to out a queer individual, and a negative one kept you hidden from the public eye. For prostitutes, not getting tested but being positive creates that kind of passing that centers around no one being aware of the stigmatizing affliction. From a health perspective, this is a nightmare. The dangers that not only the worker faces by being positive, but the risk of spreading the disease through this web of clients is apocalyptic in nature.

In the United States, there is great difficulty in discovering statistics such as these, possibly because of the secrecy with which we treat all things sexual. However, the CDC has reported that among men that prostitute for other men, 29.1% test positive for HIV, and 13.2% were positive, but unaware of their status. In the Netherlands, a study was done with over 500 people, in which 31 tested HIV positive. Of the 31, 23 were unaware of their status, making 74% of those diagnosed ignorant to their situation. With all the differences between different countries, it is heartbreaking to see a common trend being ignorance about a diagnosis as severe and frightening as HIV.

Public Opinion and Reactions

For change to occur it is required that people want it. For issues generally deemed controversial, such as illicit drug use or prostitution, the survival of those causes depend upon the public approval or disproval. Support from the collective keeps efforts alive.

In the United States, we don’t necessarily know how to tackle the issue of prostitution. Sure, states like Nevada are known for their unique choice to legalize the practice, and are rewarded handsomely through the revenue they bring in. However, on a national scale, prostitution is illegal. But, as we know from the general experience of being alive, something’s legal status rarely stops those who want it. In fact, there are some cases in which usage increases based on an illegal status. Seeing this, our best friend, Ronald Weitzer, writes in Public Control in America: Rethinking Public Policy about some of the different approaches the United States has considered taking, in order to work towards safe and legal sex work.

Indoor prostitution is an option that pops up. It is harder for a police presence to attack these agencies, forcing authorities to create elaborate tricks in order to crack down on the practice. Weitzer mentions that a single operation to go after these indoor agencies took 2 years, “costing $2.5 million (91).” He also goes on to mention a quote from a New Orleans police officer, who says, “Whenever we focus on indoor investigations, the street scene gets insane (91).” A nonenforcement policy for indoor prostitution would provide people with the services they want (and ignore are illegal), save money for the local authorities and city, and has the opportunity to get prostitutes off the street and into potentially safer situations. Weitzer does make a note of the fact that such an implementation would have to be done without “fanfare,” considering the public’s probable reaction to this new kind of sexual freedom. Again, sex and sexual behavior is a universally feared and uncomfortable topic, and social change is dependent on the public feeling.

Obviously, in the Netherlands, it is safe to assume that majority opinion is in the favor of prostitution based on what we know of its legal status and history. However, there is no place that exists without troubles. Where public opinion may be firmer where the United States is shaky, there are serious issues in the Netherlands, and the sex workers are being affected as a result of damage control. The main issue that comes up again and again is sex trafficking. Anti-sex trafficking measures being implemented sound fantastic and necessary, but it is incredibly important to realize that government intervention with sex workers generally means control, discrimination, and work restrictions. In the Netherlands, attempts to fight trafficking are directly hurting the sex industry.

Both the United States and the Netherlands have a long way to go, with dozens of little battles to fight before full acceptance and appreciation of sex work are achieved.

Conclusion

Howard S. Becker argues that there are multiple frameworks to understand deviance within. With complex issues like prostitution and sex work, the fairest assessment, I believe, it to look at deviance as the way others react to one’s own behavior. Bettie Page illustrates this perfectly. A woman with strong morals and an unshakeable belief in decency, being slut-shamed for her work as a model.

To go even further, and slut-shame those who, unlike Page ever did, actually work in the sex industry being heavily stigmatized, regardless of whatever situation brought them to their current reality. This kind of treatment does not come from nowhere. This arguably learned behavior is perpetuated throughout cultures, and stigma thrives as a result.

Sexuality is powerful, and embracing it shouldn’t be frowned upon- it should be celebrated, and allowed to grow in an environment that is safe, healthy, and welcoming.

Sources

ANTI-TRAFFICKING, M. O. (2017). SEX WORK REALITIES VERSUS GOVERNMENT POLICIES: MEANINGS OF ANTI-TRAFFICKING INITIATIVES FOR SEX WORKERS IN THE NETHERLANDS. SEX WORK REALITIES, 139.

Becker, Howard Saul. Outsiders: Studies in the Sociology of Deviance. Free Press, 1997.

Boutellier, J. C. (1991). Prostitution, criminal law and morality in the Netherlands. Crime, law and social change, 15(3), 201-211.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2017). Exchange Sex and HIV Infection Among Men Who Have Sex with Men: 20 US Cities, 2011. Retrieved from https://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/49709

Daalder, A. L. (2015). Prostitution in the Netherlands in 2014. Cahier.

Goffman, Erving. Stigma. Penguin Books, 1963.

Outshoorn, J. (2012). Policy change in prostitution in the Netherlands: From legalization to strict control. Sexuality Research and Social Policy, 9(3), 233-243.

T. Parsons, David Bimbi, Perry N. Halkitis, J. (2001). Sexual compulsivity among gay/bisexual male escorts who advertise on the Internet. Sexual Addiction &Compulsivity: The Journal of Treatment and Prevention, 8(2), 101-112.

van Veen, M. G., Götz, H. M., van Leeuwen, P. A., Prins, M., & van de Laar, M. J. (2010). HIV and sexual risk behavior among commercial sex workers in the Netherlands. Archives of sexual behavior, 39(3), 714-723.

Weitzer, R. (1991). PROSTITUTES ‘RIGHTS IN THE UNITED STATES: The Failure of a Movement. Sociological Quarterly, 32(1), 23-41.

Weitzer, R. (1999). Prostitution control in America: Rethinking public policy. Crime, Law and Social Change, 32(1), 83.

Weitzer, R. (2010). The movement to criminalize sex work in the United States. Journal of Law and Society, 37(1), 61-84.